|

Biographical Log of Michael Furstner - Page 203

09 | 10 ||

2011 :

Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec || Page :

Previous |

Next

The Martinshof Story -

A Philosophy of Happiness -

Life Awareness -

Maps & other Text series

Most Recent -

Next -

Previous -

Page 1 -

Photos -

MP3s -

Maps & Text series -

Jazclass

Monday - Wednesday, March 21 - 23 2011

(diary, D H Lawrence, absolute self)

As you no doubt have gathered, I just love the often inspiring cameo-ideas and thoughts which are one of the enjoyable characteristics of most literary novels.

As you no doubt have gathered, I just love the often inspiring cameo-ideas and thoughts which are one of the enjoyable characteristics of most literary novels.

Here is one from David Herbert Lawrence's 1915 novel The Rainbow, describing the emotional and mental growth experienced by two people when they enter into a marriage or (these days) a serious relationship.

"She had given him a new, deeper freedom. He had come into his own existence. He was born again a second time, born at last unto himself, out of the vast body of humanity.

Before he had only existed in so far as he had relations with another being. Now he had an absolute self - as well as a relative self."

(DH adds that initially it is "a very dumb, weak, helpless self, a crawling nursling.")

I like this idea of two individual selves, which expresses nicely that while still in our adolescence we are very susceptible, moulded like putty this way or that by circumstances, our environment, the people around us.

Only when we make the major life changing decision to share (possibly the rest of) our life with someone else, have we taken the first step in defining yourself as an absolute self (be it man or woman).

Also from being totally selfish (only caring for yourself) as an adolescent, we suddenly have taken on the responsibility for another person. And when our offsprings enter the world, this greater care and responsibility extends to them, so that gradually, our initial tight circle of selfishness expands, placing them (rather then yourself) in the very center.

This, in turn, expands, or rather grows, our identity as an absolute self.

Most Recent -

Next -

Previous -

Top -

Page 1 -

Photos -

MP3s -

Maps & Text series -

Jazclass

Thursday & Friday, March 24 & 25 2011

(diary, D H Lawrence, absolute self)

Upon marriage we do enter Lawrence's deeper freedom, already earlier

defined by Anthony Trollope (1815-1882) as the freedom of perfect

intimacy.

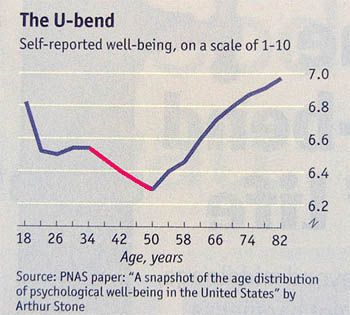

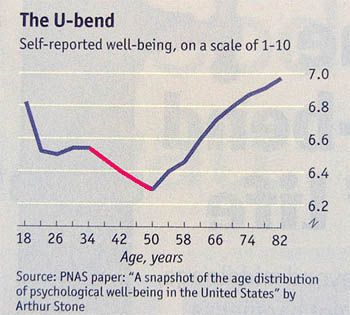

But why is it then (I ask myself) that, after only a brief period of such bliss

during our 20s (see graph below), we emotionally rapidly descent to the lowest point

of well being in our entire life?

But why is it then (I ask myself) that, after only a brief period of such bliss

during our 20s (see graph below), we emotionally rapidly descent to the lowest point

of well being in our entire life?

The answer is simple :

our absolute self (a work in progress) has (perhaps temporarily) gone out off

step with our potential self.

Imagine our potential self to be like a virtual control room (in our head)

in which a number of levers are set according to our individual likes

and dislikes, affinities and aversions, talents and ineptnesses. They also define

our degree of tolerance, motivation, determination, sociability, sexuality,

generosity, selfishness, aggression etc.

These parameters are contained within our unique genome (the DNA strings

within our chromosomes.).

Every decision we make and step we take in life towards developing our (real) absolute

self is monitored and assessed in our virtual control room.

Every decision we make and step we take in life towards developing our (real) absolute

self is monitored and assessed in our virtual control room.

If (according to John Grinde's Darwinian

Happiness theory) the action is in harmony with the genetic parameters of our

potential self, it will make us happy.

However if the assessment is negative (in

conflict with the parameters for our potential self) it will put a damper on our mood,

causing unhappiness, even depression.

As Lawrence expressed it, our initial absolute self is a "dumb, weak, helpless self". So obviously mistakes will be part

of the development process. Or circumstances may prevent us from doing the best thing.

This of course applies especially to the two environments we spend most of our life in.

Privately we may have partnered the wrong person, or at work we are

entrenched in the wrong job.

And often it is not until we reach our 40s (when our

children have flown the nest, or our financial situation has become more secure, or unhappiness has built up to an intolerable level) that we

manage to turn the corner, to grow and to convert as much as we can of our potential self's

possibility into a real absolute self.

But perhaps there is also a deeper (genetic) force at play.

Richard Dawkins (in his book "The Selfish Gene") explains that we are mere (expendable) replicators, propagating the crucial gene pool of our human species, from one generation to the next, through time.

Richard Dawkins (in his book "The Selfish Gene") explains that we are mere (expendable) replicators, propagating the crucial gene pool of our human species, from one generation to the next, through time.

This is the all overriding biological force driving us forward during that part of our lifetime during which we produce and rear our children.

Only after this crucial objective of our species' genes has been met, does this force abate, allowing our individual genetic preferences to being acted upon.

Our life time from say 20 to 40 years can therefore be seen as a period of (usually) unavoidable genetic struggle between the superior need for our species' survival and our unique personal wishes and desires.

From this perspective it is interesting to note that only a few hundred years ago a human's life expectancy (40-50 years) was barely covering the period required to produce and rear our offsprings.

Through huge discoveries in medicine, better dietary habits and life styles, we have extended our life expectancy to almost double of what it was then. This allows us now to grow more fully as (Lawrence's) individual absolute selfs realising (at least some of) our unique genetically defined characteristics.

This fills Richard

Dawkins (and me too) with hope that eventually we will be able to control our genes (instead of them controling us), so that we can "turn the selfish

process of present evolution around to a more unselfish, "altruistic" process, which in

the long term will benefit the human race as a whole."

Comments -

Most Recent -

Next Page -

Previous -

Top -

Photos -

MP3s -

Maps & Text series -

Jazclass

Copyright © 2011 Michael Furstner

|