My days in the Dutch Army (1963 - 65)

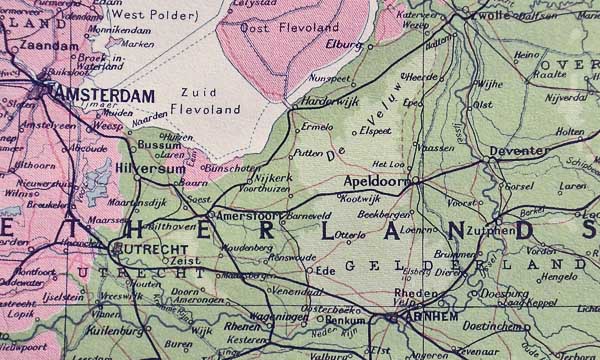

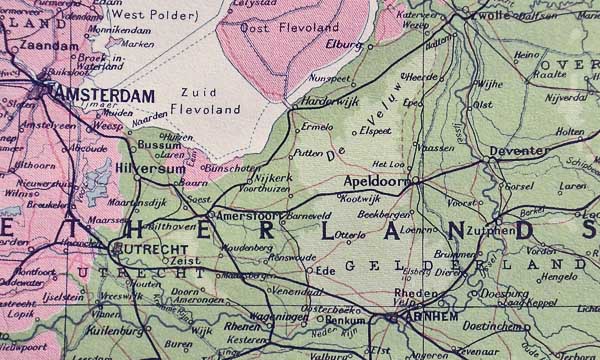

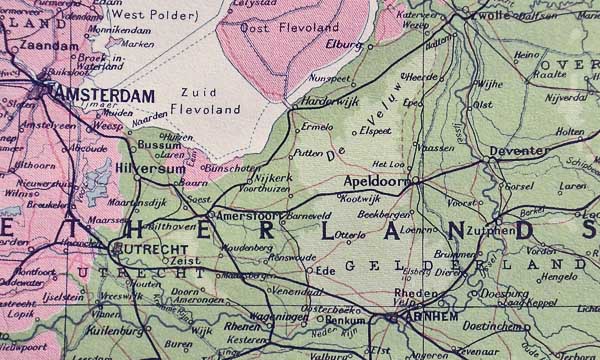

Hunt : 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - Stories - Reference map of the Netherlands

My Army days 1

My Army days 1

Those cognac glasses I talked about yesterday started me thinking about my army days.

After the war (WW2) until somewhere in the 70s there was compulsory army

training in Holland. Every young and able male had to do their service of 18

(soldiers) to 21 months (officers). You were usually called up around

your 18th birthday, but Uni students could apply for permission to complete

their studies first. So I went into the army at age 26. I did not like it at

the time I went in, but in hindsight it has been a very constructive and

indeed enjoyable time in my life.

Reserve officers in Holland were

selected purely on merit.

Joining after your studies had of course an age advantage, being more

mature than the bulk of 18-20 year olds. But there were quite a number of my

friends from Uni who never made it into or through the Officers school.

The selection process was extensive and very thorough. It started already

while still at Uni when at one point you were requested to attend a weekend

selection camp. Quite a few of my friends had done this before me already,

so I was well briefed on how to act and succeed when it was my turn. It was

in fact interesting and rather fun.

I entered the Field Artillery basic training camp

in Ossendrecht (50km SW from Breda close to the Belgian border) in November 1963 with 1500

fellow recruits. I was accommodated in one of the barracks with 199 others in

ten rooms, 20 recruits to a room. On the very first evening all 200 of us stood

shivering in our sport shorts and T shirts closely pressed together in the

entrance hall were our commanding officer, a Captain, addressed us. He

welcomed us into the army and urged us to do our best because "right here and within the next six weeks your future in the

army will be determined" he said, then added "and only 6 of you, at best will make it to the Officers

school." I still remember how very small and vulnerable I felt at

that moment.

For me the testing started right there and then, as I was immediately put in

charge of Room 10, at the very end of the barrack, and responsible for each

of the 20 recruits in it. I immediately started to get to know every one

and to put them at ease. Some were still very young and innocent. A farm

boy of barely 18 (Krikken) in the bunk below me had never left the

family farm and always worn wooden clogs. So for the first week I tied his

boot laces every morning until he could do it himself. "What is this for ?"

he asked, holding up a hankie. I explained it to him.

Within a

week we worked and acted as a well synchronised unit, snapping to attention

on my command, marching crisp and sharp, putting every other room in the

building to shame. A young wachtmeester (Dutch title for a Sergeant in the

Artillery) was the instructor for our room. He was tough, matter of fact,

but very effective and I liked him. Without letting on I think he was

pleased with our progress, but discharged me from my "command" after just

two weeks, the first one of the 10 rooms. Was this a good or a bad sign I

wondered.

During those first six weeks we went through the usual basic training

routines, marching, running, night patrols, riffle routines. Skill testing

also continued and I had an interview with the army psychologist Major

Waterman.

On the morning of January 10, at 6am when we were all packed

up and ready for a 10 km hike through the snow, the loudspeaker suddenly

called out my name. I had to report immediately to the command post at the

front gate. When I arrived there, quite out of breath, I was informed my wife was in

labour and given a pass for 3 days of compassionate leave. I rushed back to

the barrack, threw my gear into its locker, wished my envious mates a "long

and pleasant hike" and was on my way. After a two and a half hour journey in

bus and trains my father was waiting for me at the Zutphen Railway

Station. "Welcome son", he said "You have become a father.". Babette had

entered this world.

Three days later I was back in camp. That evening I shouted several cases

of beer in the mess to all 20 of my room mates. We had a hell of a party.

Later back at the barrack the toilet was a real mess as several of the guys

had vomited all over it. Two or three of us cleaned it all up before our

wachtmeester, always on the prowl at night, got a sniff of it.

A few

weeks later I climbed with my kit into the back of a truck to Breda.

I had been selected as one of the six from our barrack to be admitted to the

SROA, the School for Reserve Officers of the Artillery. A total of 52

of the 1500 recruits would arrive there that day. Only 36 of us would, 6

months later, successfully complete the course.

Up - Top - Down

My Army days 2

My Army days 2

We arrive at the School

for Reserve Officers in the Artillery (SROA) in Breda late in the morning (January '64),

and after having our gear properly stored away in our lockers in the

sleeping quarters we go straight in for lunch. Conditions at the school are

quite different from those at the base camp. Beds instead of 2 story bunks,

central heating and white table cloths, proper plates, cups and saucers,

glasses in the dining room, where servants in spotlessly white jackets serve

up our meals.

The Head of the School, a tall robust Lieutenant

Colonel, joins us for lunch. After a few words of welcome he briefly states

the two simple but important rules which must not be broken in the school.

The first one needs no explanation : Being on time

always means 5 minutes early !.

"The fundamental and

absolutely essential function of an officer in the army," he continues "is

to make decisions. And you will start doing that right here and now.

Every time you make a good decision we will be very happy, and every time

you make a bad decision we will be very unhappy, but we will forgive you!

But fail to make a decision at all and you will

be dismissed from this school instantly !"

This is without a doubt the single most important

lesson I have ever learned, because it applies not just to the army,

but to the way you conduct your entire life. Making a decision in life is

not an isolated black and white proposition. Decision making is a skill

which needs to be learned through practice. It is very much a percentage

game, the more used you become to making decisions the higher the

percentage rises of the successful outcomes.

There is an enormous amount to learn at the SROA, all

cramped into just 6 months. At the end of every 2 months there is a

full week of tests and examinations, both in writing and practical. If you

fail your are dismissed from the school and return to the regular army

as a Private. If you pass you progress to the next 2 months training.

Each time you pass you are also promoted in rank. First from Private to

Corporal, then to Wachtmeester (Artillery equivalent to Sergeant), finally

after successfully completing the whole course to Cornet (accepted as

officer but not yet commissioned).

There are different teaching streams for the various specialist

officer positions : truck and car repairs, communications, surveyors,

observers (based with the Infantry at the front line directing the artillery

fire) and battery officers (BTOs), in charge of an entire Field Artillery

Battery.

I go through the BTO stream. A Battery consists of six 105mm

Howitzers, about 25 cars and trucks and 80 to 100 officers, noncoms and

privates. As BTO you have to supervise every single aspect of the battery.

Including for example : maintenance of rifles, guns, radios, cars. You have

to develop skills in radio communication, surveying. You also need to be

able to train the soldiers under your command on every aspect of their

duties.

Probably the most important skill I learn is the gun fire control

calculation. You have to compute the gun inclination and direction in order

to correctly aim at and hit the target. This is a complicated procedure involving the weather

conditions at various successive air levels the projectile is to travel

through, temperature of the explosives, calibration for each gun, etc.etc.

I very much enjoy doing these. The calculated base values are marked on a

slide ruler, which can then used to read the required gun barrel

inclinations for specific targets.

At the time I went through the School we are just changing over from 25

Pounders to 105mm Howitzers. The 25 Pounder is a lovely gun. It

is small and compact and can rotate easily around on its circular base.

Calculations are done using the old 360 degrees of the compass.

At the time I went through the School we are just changing over from 25

Pounders to 105mm Howitzers. The 25 Pounder is a lovely gun. It

is small and compact and can rotate easily around on its circular base.

Calculations are done using the old 360 degrees of the compass.

The 105

Howitzer has two legs which have to be spread and dug in when placed in

position, and can therefore not shift around as easily and quickly as the

25 Pounder. It has however a much larger inclination range (able to point steeply upwards, essential in

mountainous terrain) and is calibrated to the new 4000

thousands compass division. This makes calculations much easier, as it

converts 90 degrees of the old system into the equivalent of 1000

thousands.

The Captain in charge of our progress is a blond square

headed man with glasses in his mid 30s. He is much feared as out of the

previous group he guided through the School less than half managed to

graduate at the end. We are all therefore much on our metal. He also marries during our term (as one of the elected Class representatives I attend his wedding) which no doubt helps to mellow his attitude in life. This

all helps as 36 from the 52 who initially started in our group successfully graduate as Cornets.

I become somewhat personally involved with the Lieutenant

Colonel Head of the School. He discovered at one point that we have an important thing in

common. Both he and I have married wives with incompatible blood groups, one

being Rhesus factor positive the other negative. This can cause

problems when our children are born. His wife has given birth to three

children. Two of them survived without a problem, but the third one is

stillborn. He warns me about this.

Our eldest daughter Babette

is fine. But I am reminded of his words six years later when our son

Jeroen is born in Kalgoorlie (Western Australia). He

receives several blood transfusions immediately after his birth, and also spends the first 6

months of his life in a most ingenious frame to properly realign his hips.

After that, thanks goodness, he is fine.

During the farewell party after our successful completion

of the course I share a drink with the boss, and in my youthful enthusiasm

try to give him some advice on one of the last training exercises we have

just gone through. "Who the hell do you think is in charge of this

School!" he bellows at me, "You or me??".

But it is a good

natured rebuke, almost like a father to his son. For he surely must smile

inwardly, as he realises one thing for sure : I have got a firm hold on that

second School rule of his and will adhere to it for the rest of my life.

PS

Computers have replaced the humble Artillery slide ruler long ago, and the

SROA too has closed its doors after National service was abandoned in the

Netherlands. To me that makes these memories of days gone bye even more dear

and valuable.

Up - Top - Down

My Army days 3

We stay in Assen for the remaining 14 months period of my National

service until late August 1965. Life with the regular troops is far less

hectic than my previous 8 months of

concentrated training.

Most of the time is taken up with maintenance of

equipment, short trips out in the field and training of the personnel. At

intervals the routine is livened up by longer exercises, camping in the

field for 3, 4 days or a week, either at the shooting grounds at

Oldenbroek near the village of Ermelo (Veluwe, Gelderland) or

at Münsterlage on the Lüneburger Heide (North of

Celle, Germany) and close to the Iron Curtain.

Immediately on arrival

from the SROA I am attached to the staff, rather

than being a battery officer (for which I was trained). This suits me fine, as I am not really a

marching and drilling new recruits type of person.

Initially I am attached to the S3, the

Commander of Operations, and work in the Afdeling Command Post with the fire

calculations team, providing targets for all three gun batteries in the

Afdeling.

I am also involved in the retraining of professional officers from

the recently abandoned Dutch Anti Aircraft Artillery units ("Lucht

Artillery"), which have been transferred to us, the Field Artillery. It is

quite fun, after being bossed around for 6 months by wachtmeesters (= Artillery sergeants) at the

Artillery School, to now be on the other side of the equation, supervising

Captains and Majors who are sweating it out over shooting procedures.

In due course I am transferred to the Intelligence section and after

a brief period become the S2 in charge of Security and Intelligence

for the Afdeling. In peace time this is a lot less exiting than it sounds.

Apart from compiling data from various sources during field exercises for

defining appropriate shooting targets for the batteries, it is a rather

administrative job. Looking after politically "suspect" soldiers who have in the past

read a Communist pamphlet or two, and are now barred from promotion, unless

screened by me and approved by Headquarters in Den Haag. Generally this can

be done and I am successful in several cases. I am also in charge of

all maps used by the Afdeling. These are thousands of NATO classified maps

(held in several boxes under lock and key) in case of war, but also the

regular stock used during exercises in the field. The Dutch Army has a firm

policy : maps are never ever lost!. But as it are really great maps

it is no surprise that they do get "lost" amongst various interested

personnel.

The standard solution is simple. Whenever an Army map is reported

"lost" I take another map of my stock, rip it in half, present both pieces to

the map supply center in Ede and immediately receive two brand new maps in exchange. Works every

time ! For it is of course unavoidable that maps become damaged or worn during

use.

Up - Top - Down

My Army days 4 (Final)

Besides my official functions in the Army I also have an important social

one. Soon after arriving in Assen I am appointed Mess President in the

Field, in charge of the Officers field mess whenever we are on exercises

within our Country. During exercises on foreign soil (mainly Germany) a

professional officer (instead of a reserve like me) is mandatory for that

function.

This job is quite fun. I am in charge of a three ton truck, a

driver and two mess servants. The truck contains a large mess tent, folding

tables, chairs, table cloths, plates, cutlery, glasses and a suitable

quantity of alcohol, soft drinks and nibble foods. The two mess servants and

I jointly purchase the consumables from an Army base mess, then sell them

with a small markup on to the officers. All consumptions go on individual

slates, which I later present and collect from each once we are back in

Assen. We always manage to break even and usually make a small profit which

we share amongst the three of us.

Dur

ing the day I fulfill my normal

operational responsibilities while the two mess servants guard our

"investments". I usually manage to get back early, often to go out again and

purchase fresh supplies. At night I stay in the mess until the last

customer leaves, which on occasion can be at 5am. Most nights I sleep on a

table in the mess tent, right on top of our precious supplies, for the

saying goes that "The Cavalry may be the Queen of the

battle, but the Artillery is the King of the bottle !"

We regularly go on exercises in Germany, sometimes on our own, sometimes in

combination with other NATO country Army units. The Artillery exercise area,

called Münsterlage, is located in the Southern half of the Lüneburger Heide, North

of Celle. Celle has a Duty Free US Army store which we are

allowed to use, and always do to load up on cheap perfumes, alcohol, etc. to

take with us back home.

The Artillery area itself has a shooting target

pit in its center with plenty of ground surrounding it for shifting battery

positions around and for base camp areas. On its Eastern side the area

extends right up to the Iron Curtain, a 150 meters wide zone that

cuts through the forest. All trees and bushes are cleared, like an super

wide Australian fire break, and a high barbed wire fence on either side

prevents anyone from entering the bare stripped zone which is densely

mined.

On one of our last trips to this area we set up our base

camp right alongside the Iron Curtain. One day we conduct a 36 hours non

stop exercise through continued rain. We are all wet and miserably cold

when we get back to camp. I change clothes and enter the Officers Mess tent.

My friend Potter is there and we start drinking together, Pimms

Nr.1 with something added to make it "a bit more potent".

Potter, a Reserve Officer like me, is in charge of maintenance of the Afdeling's entire

car fleet, a massive collection of over 100 trucks, jeeps, etc. He really

has his work cut out and is doing a terrific job, as is recognised by all.

Tonight, as the Pimms cocktails start to take effect, Potter and I are not just

friends, no we have become brothers, and we should have more brothers we

both agree. There must be more potential brothers around, here but also those

poor buggers on the other side of the fence! I am not sure what our

motivation was, to fight or to befriend them, but at around 2am we leave the

Mess tent and stumble arm in arm towards that high Iron Curtain fence and start to climb

it.

We must be making plenty of noise, for it wakes up my Guardian

Angel, the Opper Wachtmeester (= Artillery Sergeant Major) of the S3

staff. I always looked after him, and he after me. These are the vital

protective connections one builds up in institutions like the Army. The

"Opper" gets out of his tent and sees us hanging there, halfway up,

entangled in the barbed wire. He plucks us off the bloody fence like a pair

of over ripe cherries and puts us to bed. The next morning, bleary eyed, I

thank him. He just smiles, says not a word.

Finally I reach

the end of my service. A few weeks before all Reserve Officers from our SROA

class that have survived, meet up together for our Commissioning

ceremony. We have a choice of either swearing or promising allegiance to

our Dutch Queen. I make my promise. Finally I reach

the end of my service. A few weeks before all Reserve Officers from our SROA

class that have survived, meet up together for our Commissioning

ceremony. We have a choice of either swearing or promising allegiance to

our Dutch Queen. I make my promise.

Afterwards there is a reception in the Historic Artillery Officers

Mess on our shooting grounds Oldenbroek (near Ermelo).

Amongst the many

familiar young faces around me, an older Officer I recognise approaches me.

It is Major Waterman who interviewed me

21 months ago as a recruit in Ossendrecht. "Congratulations Lieutenant Furstner, you made it" he

says while we shake hands. "You know, it is quite

remarkable," he continues, since we last met

almost 2 years ago, I have interviewed about 3000 recruits like you. I have

forgotten all of them. But you, I will always remember!". We share a

drink on that. How vain we are. Because of his kind and so very

flattering words, I will never forget him either.

PS

After just under 3 years, when I was in Australia, I was automatically promoted to First Lieutenant in the Artillery. I found amongst my papers the Official Notification of that fact. Those Reserve Officers that resided in the Netherlands were in due course called up for a 6 week refresher course, after which they were promoted to Captain. Unfortunately I remained overseas and was therefore unable to attain that rank.

After just under 3 years, when I was in Australia, I was automatically promoted to First Lieutenant in the Artillery. I found amongst my papers the Official Notification of that fact. Those Reserve Officers that resided in the Netherlands were in due course called up for a 6 week refresher course, after which they were promoted to Captain. Unfortunately I remained overseas and was therefore unable to attain that rank.

Top of Page

© 2010-2011 Michael Furstner

|